- in Adventure, Alamut, Asia, assassination, assassins, books, castles, crime, culture, cynicism, death, Europe, European fiction, European literature, European novels, fiction, Fiction in English, forts, Hasan, Hostages, Islam, Ismailis, kidnapping, killing, literature, Literature in English, loyalty, murder, murderers, Muslims, Novel, novel from every country, novels, novels in English, Omar Khayyam, radicalism, reading, Reading 1 book from every country, Reading 1 novel from every country in the world, Reading the world, religion, review, Slovenia, Slovenian fiction, Slovenian literature, Slovenian novels, suicide, terrorism, terrorists, Violence, world, world literature, writing

- Leave a comment

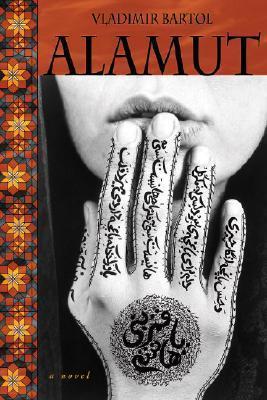

Book 160: Slovenia (English) – Alamut (Vladimir BARTOL)

“I come from al-Ghazali, Your Excellency, with this letter.”

He held the letter out toward the old man, while calmly drawing the sharpened writing instrument out of it. He did this so naturally that none of those present was aware of the action.

The vizier unsealed the envelope and unfolded the letter.

”What is my learned friend up to in Baghdad?” he asked.

Ibn Tahir suddenly leaned forward and shoved the dagger into his throat beneath the chin. The vizier was so startled that for the first few moments he didn’t feel any pain. He just opened his eyes up wide. Then he scanned the only line of the letter one more time and grasped everything.

My Slovenian novel, which has apparently been a bestseller in many languages (seemingly not in English, though it should be) really has as little as is imaginable to do with Slovenia (which is by the way my favourite country in Europe at the moment). It is totally removed in both time and place, like my preceding Macedonian novel. It is derived from one of the more fascinating tales from Marco Polo’s generally prosaic Travels, that of the Old Man of the Mountain, but the Ismaili stronghold in modern Iran actually existed.

Bartol takes three young friends, sworn to friendship, who each choose different paths in life. One becomes a vizier, one (Omar Khayyam) a poet, and the third, the subject of the story, Hasan, becomes what we would now see as the head of a terrorist organisation. Hasan becomes so cynical that he can not believe in anything at all – his ultimate motto is “Nothing is true, everything is permitted;” he reveals it only to his most trusted confidantes, and basically applies it to no one but himself. Everyone else is treated more or less as a child, as his tool. Hasan (known to his followers as Sayyiduna ‘Our Lord’), sets out to deceive and exploit them, by creating a fairy tale and making it seem real to them. He reproduces in reality at his castle (Alamut) the Muslim paradise, and rewards his most trustworthy followers with a single night there (after drugging them with opium), so that they can be used as assassins (a word which derives from hashishim ‘opium-eaters’) against his enemies. Despite some close calls, as far as we learn from the novel his plan is successful. Yet its eternal vulnerability is obvious, throughout symbolised by the lift he uses, which his trusted eunuchs could easily use to kill him. (As generally with terrorist organisations, the success at murdering enemies was matched by abject failure at conquering them – and Alamut was to fall to the Mongols in 1256). Bartol wrote a long time before the age of Al-Qaida, but his sophisticated insight into the mindset of a terrorist warlord and what are now suicide bombers is more relevant now than ever before. Alamut can be read merely as a popular novel, but there is so much food for thought that its worth is far deeper than that.

Vladimir BARTOL (1903 – 1967), Alamut, translated from Slovenian by Michael Biggins, Berkeley, CA, North Atlantic Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-55643-681-9

Recent Posts

- Book 249: Somaliland (English) – The Orchard of Lost Souls (Nadifa MOHAMED)

- Book 248: St Helena, Ascension & Tristan da Cunha (English) – Napoleon’s Last Island (Thomas KENEALLY)

- Book 247: Montserrat (English) – The Three Suitors of Fred Belair (E.A. MARKHAM)

- Book 246: Punjab (English) – Saintly Sinner = Pavitra Paapi (Nanak Singh)

- Book 245: Easter Island/Rapa Nui (English) – Easter Island (Jennifer VANDERBES)

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- February 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

Categories

- 'Journey to the West'

- 'Monkey'

- Abdulrazak Gurnah

- Adventure

- Afghan fiction

- Afghan literature

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- African books

- African fiction

- African literature

- African novels

- air force

- Alamut

- Albania

- Albanian fiction

- Albanian literature

- Albanian novels

- Albinos

- Algeria

- Algerian fiction

- Algerian literature

- alienation

- Alzheimer's

- Amazon

- American fiction

- American Samoa

- American Samoan books

- American Samoan fiction

- American Samoan literature

- American Samoan novels

- Amerindians

- Ancient Egypt

- Ancient Rome

- Andorra

- Andorran books

- Andorran fiction

- Andorran literature

- Andorran novels

- Angels

- Angola

- Angolan fiction

- Angolan literature

- Anguilla

- Anguilla books

- Anguilla fiction

- Anguilla literature

- Anguilla novels

- animals

- Antarctica

- Antarctica fiction

- Antarctica literature

- Antarctica novels

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Antigua and Barbuda books

- Antigua and Barbuda fiction

- Antigua and Barbuda literature

- Antigua and Barbuda novels

- apartheid

- Arabia

- Arabic fiction

- Arabic literature

- Arabs

- Aramaic

- Arctic

- Argentina

- Argentine fiction

- Argentine literature

- Argentinian fiction

- Argentinian literature

- Armenia

- Armenian fiction

- Armenian literature

- Armenian novel

- Armenians

- Army

- arranged marriages

- art

- artists

- Aruba

- Aruba books

- Aruba fiction

- Aruba literature

- Aruba novels

- Asia

- Asian books

- Asian fiction

- Asian literature

- Asian novels

- assassination

- assassins

- Asturias

- atom bombs

- atomic testing

- Auguries

- Austen

- Australia

- Australian books

- Australian explorers

- Australian fiction

- Australian literature

- Australian novels

- Austria

- Austrian fiction

- Austrian literature

- Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Azerbaijan

- Azerbaijan fiction

- Azerbaijan literature

- Bahamas

- Bahamian fiction; Bahamian literature; Bahamian novels

- Bahrain

- Bahrain fiction

- Bahrain literature

- Bahrain novel

- bananas

- Bangladesh; Bangladeshi literature; Bangladeshi fiction

- banned books

- Barbados

- Barbados books

- Barbados fiction

- Barbados literature

- Barbados novels

- Barcelona

- Bön

- Bedouin

- Belarus

- Belarus fiction

- Belarus literature

- Belgian fiction

- Belgian literature

- Belgium

- Belize

- Belize fiction

- Belize literature

- Belize novels

- Benin

- Benin fiction

- Benin literature

- Bermuda

- Bermudan books

- Bermudan fiction

- Bermudan literature

- Bermudan novels

- betrayal

- Bhutan

- Bhutanese fiction

- Bhutanese literature

- Bhutanese novels

- Bildungsroman

- blindness

- Bolivia

- Bolivian books

- Bolivian fiction

- Bolivian literature

- Bolivian novels

- bombing

- Booker Prize

- books

- Books in English

- books in French

- books in Spanish

- Bosnia-Herzegovina

- Bosnia-Herzegovina fiction

- Bosnia-Herzegovina literature

- Bosnia-Herzegovina novels

- Botswana

- Botswana fiction

- Botswana literature

- Botswana novel

- Bougainville books

- Bougainville fiction

- Bougainville literature

- Bougainville novels

- boys

- Brazil

- Brazzaville

- bridges

- British fiction

- British Isles

- British novels

- British Virgin Islands

- British Virgin Islands books

- British Virgin Islands fiction

- British Virgin Islands literature

- British Virgin Islands novels

- brothers

- Brunei

- Brunei fiction

- Brunei literature

- Brunei novels

- Buddhism

- Bulgaria

- Bulgaria fiction

- Bulgaria literature

- Burkina Faso

- Burkina Faso fiction

- Burkina Faso literature

- Burma

- Burmese fiction

- Burmese literature

- Buru Quartet

- Burundi

- Burundi fiction

- Burundi literature

- Cabo Verde

- Cairo Trilogy

- Cambodia

- Cambodian fiction

- Cambodian literature

- Cameroon

- Cameroonian fiction

- Cameroonian literature

- Canada

- Canadian fiction

- Canadian literature

- canals

- cancer

- canoes

- Cape Verde

- Cape Verde fiction

- Cape Verde literature

- Cape Verde novels

- Caribbean

- Caribbean books

- Caribbean fiction

- Caribbean literature

- Caribbean novels

- castles

- Catalan fiction

- Catalan literature

- Catalonia

- Cathedrals

- Catholic Church

- cats

- cattle rustling

- Caucasus

- Cayman Islands

- Cayman Islands books

- Cayman Islands fiction

- Cayman Islands literature

- Cayman Islands novels

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Côte d'Ivoire fiction

- Côte d'Ivoire literature

- Ceauşescu

- Central African Republic

- Central African Republic fiction

- Central America

- Central American fiction

- Central American literature

- Central American novels

- Central Asia

- Central Asian fiction

- Central Asian literature

- Cervantes

- Chaco War

- Chad

- Chad fiction

- Chad literature

- Chechnya

- Chechnya fiction

- Chechnya literature

- Chechnya novels

- child brides

- child marriage

- Child of All Nations

- child soldiers

- Childhood

- children

- Chile

- Chile books

- Chile fiction

- Chile literature

- Chile novels

- Chilean fiction

- Chilean literature

- China

- Chinese books

- Chinese fiction

- Chinese literature

- Chinese novels

- cholera

- Chopin

- Christ

- Christa Wolf

- Christianity

- Christians

- circumnavigation

- citizenship

- civil war

- class struggle

- Classics

- climate change

- Coal

- Colombia

- Colombian fiction

- Colombian literature

- Colombian novels

- Colonialism

- colonies

- colonisation

- coming of age

- communism

- Comoros

- Comoros fiction

- Comoros literature

- Comoros novels

- concentration camps

- Congo

- Congo books

- Congo fiction

- Congo literature

- Congo novels

- Congo Republic

- Congo-Brazzaville

- conmen

- Cook Islands

- Cook Islands books

- Cook Islands fiction

- Cook Islands literature

- Cook Islands novels

- cooking

- coroners

- corpses

- Costa Rica

- Costa Rica fiction

- Costa Rica literature

- coups d'état

- cowboys

- crime

- Crime and Punishment

- Crime and Punishment; Dostoyevsky; Russian fiction; Russian literature; Russia; crime; murder

- Croatia

- Croatian fiction

- Croatian literature

- cruelty

- Cuba

- Cuba fiction

- Cuba literature

- Cuban books

- Cuban literature

- Cuban novels

- culture

- culture clash

- culture shock

- cynicism

- Cypriot fiction

- Cypriot literature

- Cypriot novels

- Cyprus

- czars

- Czech fiction

- Czech literature

- Czech Republic

- Czech Republic fiction

- Czech Republic literature

- Czechoslovakia

- Czechoslovakia fiction

- Czechoslovakia literature

- Dahomey

- Dahomey fiction

- Dahomey literature

- Danish fiction

- Danish literature

- death

- deception

- decipherment

- decolonisation

- delinquents

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- Democratic Republic of Congo fiction

- Democratic Republic of Congo literature

- Denmark

- deserters

- desertification

- desertion

- deserts

- detective stories

- detectives

- detention camps

- Dictatorship

- Difaqane

- dinners

- diplomats

- disappearance

- disease

- divorce

- Djibouti

- Djibouti fiction

- Djibouti literature

- Djibouti novels

- doctors

- Dominica

- Dominican books

- Dominican fiction

- Dominican literature

- Dominican novels

- Dominican Republic

- Dominican Republic fiction

- Dominican Republic literature

- Don Quijote

- Dostoyevsky

- drought

- Dubai

- Dutch East Indies

- Dutch fiction

- Dutch literature

- Dutch novels

- dying

- dystopias

- East Africa

- East African fiction

- East African literature

- East German fiction

- East German literature

- East Germany

- East Timor

- East Timorese fiction

- East Timorese literature

- East Timorese novels

- East Turkistan

- Easter Island

- Easter Island books

- Easter Island fiction

- Easter Island literature

- Easter Island novels

- Ecuador

- Ecuador fiction

- Ecuador literature

- Ecuadorian fiction

- Ecuadorian literature

- education

- Egypt

- Egyptian fiction

- Egyptian literature

- El Salvador

- El Salvador fiction

- El Salvador literature

- elections

- electoral fraud

- emancipation

- Emigration

- empires

- England

- English classics

- English fiction

- English literature

- English novels

- epic poetry

- epidemics

- Equatorial Guinea

- Equatorial Guinea books

- Equatorial Guinea fiction

- Equatorial Guinea literature

- Equatorial Guinea novels

- Eritrea

- Eritrea books

- Eritrea fiction

- Eritrea literature

- Eritrea novels

- Errol Flynn

- escape

- espionage

- Estonia

- Estonian fiction

- Estonian literature

- Estonian novels

- eSwatini

- eSwatini fiction

- eSwatini literature

- eSwatini novels

- Ethiopia

- Ethiopian fiction

- Ethiopian literature

- ethnography

- Europe

- European books

- European fiction

- European literature

- European novels

- exile

- expeditions

- exploitation

- Exploration

- explorers

- eyes

- Falkland Islands

- Falklands War

- families

- family secrets

- famine

- fantasy

- Fathers

- Faxian

- Federated States of Micronesia

- feminism

- fiction

- fiction in Dutch

- Fiction in English

- fiction in Esperanto

- Fiction in French

- Fiction in German

- fiction in Italian

- fiction in Norwegian

- fiction in Portuguese

- fiction in Russian

- Fiction in Spanish

- fiction in Swedish

- fidelity

- Fiji

- Fijian fiction

- Fijian literature

- Fijian novels

- filibusters

- Filipinas

- Filipinos

- film stars

- filmmakers

- Finland

- Finnish fiction

- Finnish literature

- First World War

- fishing

- Flaubert

- football

- Footsteps

- forts

- foster fathers

- France

- Francophone African literature

- fraud

- French books

- French classics

- French fiction

- French Guiana

- French Guiana books

- French Guiana literature

- French Guiana novels

- French literature

- French Polynesia

- French Polynesian books

- French Polynesian fiction

- French Polynesian literature

- French Polynesian novels

- friendship

- Full Circle

- fundamentalism

- Gabon

- Gabon books

- Gabon fiction

- Gabon literature

- Gabon novels

- Gambia

- Gambian fiction

- Gambian literature

- Gambian novels

- gangs

- Gaols

- Gardening

- Gardens

- gauchos

- gay life

- gender politics

- genetic deformities

- genocide

- geologists

- geology

- Georgia

- Georgian fiction

- Georgian literature

- Georgian novels

- German Democratic Republic

- German fiction

- German literature

- Germany

- Ghana

- Ghanaian fiction

- Ghanaian literature

- ghosts

- Gina Nahai

- glaciologists

- glaciology

- Goa

- Goan fiction

- Goan literature

- Goan novels

- Godan

- Gossip

- grandmothers

- Great Britain

- Greece

- Greek fiction

- Greek literature

- Greeks

- Greenland

- Greenland books

- Greenland fiction

- Greenland literature

- Greenland novels

- Grenada

- Grenada books

- Grenada fiction

- Grenada literature

- Grenada novels

- griots

- Guadeloupe

- Guadeloupe books

- Guadeloupe fiction

- Guadeloupe literature

- Guadeloupe novels

- Guam

- Guam books

- Guam fiction

- Guam literature

- Guam novels

- Guatemala

- Guatemalan fiction

- Guatemalan literature

- guerrillas

- Guinea

- Guinea books

- Guinea fiction

- Guinea literature

- Guinea novels

- Guinea-Bissau

- Guinea-Bissau books

- Guinea-Bissau fiction

- Guinea-Bissau literature

- Guinea-Bissau novels

- gulags

- Guyana

- Guyana fiction

- Guyana literature

- Guyana novels

- Haiti

- Haitian fiction

- Haitian literature

- Hajj

- Hasan

- Hatred

- Hawaii

- Hawaiian fiction

- Hawaiian literature

- Hawaiian novels

- Hedin

- Herta Müller

- Historical fiction

- Hmong

- Hmong fiction

- Holocaust

- Holy See

- homeless people

- homelessness

- Homer

- Homosexuality

- homosexuals

- Honduras

- Honduras fiction

- Honduras literature

- Hong Kong

- Hong Kong fiction

- Hong Kong literature

- honour killings

- hospitals

- Hostages

- House of Glass

- houses

- Hugo

- humour

- hunchback

- Hungarian literature

- Hungary

- Hungary fiction

- hunger

- Huns

- hurricanes

- Iceland

- Icelandic books

- Icelandic fiction

- Icelandic literature

- Icelandic novels

- Identity

- illegal immigration

- imagination

- Immigration

- indentured labor

- indentured labour

- independence

- India

- Indian books

- Indian fiction

- Indian literature

- Indian novels

- Indian Ocean novels

- Indonesia

- Indonesian fiction

- Indonesian literature

- Indonesian politics

- infidelity

- Inner Mongolia

- Inner Mongolian books

- Inner Mongolian fiction

- Inner Mongolian literature

- Inner Mongolian novels

- Insanity

- intellectuals

- inter-oceanic canal

- interrogation

- Intolerance

- Iran

- Iranian books

- Iranian fiction

- Iranian literature

- Iranian novels

- Iraq

- Iraqi fiction

- Iraqi literature

- Ireland

- Irian Jaya

- Irish fiction

- Irish literature

- Isla de Pascua

- Islam

- islands

- Isle of Man

- Isle of Man books

- Isle of Man fiction

- Isle of Man literature

- Isle of Man novels

- Ismailis

- Israel

- Israel fiction

- Israel literature

- Italian fiction

- Italian literature

- Italy

- Ivoirian fiction

- Ivory Coast

- Ivory Coast fiction

- Ivory Coast literature

- Jails

- Jamaica

- Jamaican fiction

- Jamaican literature

- Jamaican novels

- Japan

- Japanese

- Japanese fiction

- Japanese gardens

- Japanese literature

- Jesus

- Jews

- Jordan

- Jordan fiction

- Jordan literature

- journalism

- journalists

- journeys

- Judaism

- Kampuchea

- Kashmir

- Kashmir fiction

- Kashmir literature

- Kazakh fiction

- Kazakh literature

- Kazakhstan

- Kazantzakis

- Kenya

- Kenyan fiction

- Kenyan literature

- Khalistan

- Khazars

- Khmer Rouge

- kidnapping

- killing

- kings

- Kiribati

- Kiribati books

- Kiribati fiction

- Kiribati novels

- kites

- Korean fiction

- Korean literature

- Korean War

- Kosovar fiction

- Kosovar literature

- Kosovar novels

- Kosovo

- Kurdish fiction

- Kurdish literature

- Kurdistan

- Kurds

- Kuwait

- Kuwait fiction

- Kuwait literature

- Kvachi

- lamas

- Lampedusa

- landlords

- landowners

- landslides

- language

- Laos

- Laos fiction

- Laos literature

- Latin America

- Latin American books

- Latin American fiction

- Latin American literature

- Latin American novels

- Latvia

- Latvian fiction

- Latvian literature

- Latvian novels

- Lebanese fiction

- Lebanese literature

- Lebanon

- Lesotho

- Lesotho fiction

- Lesotho literature

- Lesotho novel

- Lessing

- leukaemia

- Liberia

- Liberian fiction

- Liberian literature

- Libya

- Libyan fiction

- Libyan literature

- Liechtenstein

- Liechtenstein books

- Liechtenstein fiction

- Liechtenstein literature

- Liechtenstein novels

- lies

- literature

- literature in Dutch

- Literature in English

- literature in Esperanto

- literature in French

- Literature in German

- literature in Italian

- literature in Portuguese

- literature in Russian

- Literature in Spanish

- Lithuania

- Lithuanian fiction

- Lithuanian literature

- Lithuanian novels

- llanos

- loneliness

- Lop Nor

- Loulan

- Love

- loyalty

- Lusophone literature

- Luxembourg

- Luxembourg fiction

- Luxembourg literature

- Luxembourg novels

- Macau

- Macau fiction

- Macau literature

- Macau novel

- Macedonia

- Macedonian fiction

- Macedonian literature

- Macedonian novels

- Madagascar

- Madagascar fiction

- Madagascar literature

- Madness

- magic

- Magical realism

- maids

- Malawi

- Malawi fiction

- Malawi literature

- Malaysia

- Malaysian fiction

- Malaysian literature

- Maldives

- Maldives books

- Maldives fiction

- Maldives literature

- Maldives novels

- Mali

- Mali books

- Mali fiction

- Mali literature

- Mali novels

- Malta

- Maltese fiction

- Maltese literature

- Maltese novels

- Malvinas

- Man Booker Prize

- Maori

- Margaret Atwood

- marine biologists

- marine biology

- Marriage

- Marshall Islands

- Marshall Islands books

- Marshall Islands fiction

- Marshall Islands literature

- Marshall Islands novels

- massacres

- Mauritania

- Mauritanian books

- Mauritanian fiction

- Mauritanian literature

- Mauritanian novel

- Mauritian fictiion

- Mauritian literature

- Mauritian novels

- Mauritius

- Mayotte

- Mayotte books

- Mayotte fiction

- Mayotte literature

- medical procedures

- medicine

- Melanesia

- Melanesian books

- Melanesian fiction

- Melanesian literature

- Melanesian novels

- memory

- mental illness

- mercy

- Mexican fiction

- Mexican literature

- Mexico

- Micronesia

- Micronesia books

- Micronesia fiction

- Micronesia literature

- Micronesia novels

- Middle East

- Middle Eastern fiction

- Middle Eastern literature

- Middle Eastern novels

- mines

- Mining

- misanthropy

- Missing people

- Missing persons

- missionaries

- misunderstandings

- Moldova

- Moldovan fiction

- Moldovan literature

- Moldovan novels

- Monaco

- Monaco books

- Monaco fiction

- Monaco literature

- Monaco novels

- monarchs

- Mongolia

- Mongolian fiction

- Mongolian literature

- Mongolian novels

- monks

- Montenegrin fiction

- Montenegrin literature

- Montenegrin novels

- Montenegro

- Montserrat

- Montserrat book

- Montserrat books

- Montserrat fiction

- Montserrat literature

- Montserrat novels

- Moonlight on the Avenue of Faith

- Moroccan fiction

- Moroccan literature

- Morocco

- Mossad

- Mothers

- Mozambique

- Mozambique fiction

- Mozambique literature

- multiculturalism

- murder

- murder-suicide

- murderers

- Muslims

- mutes

- Myanmar

- Myanmar fiction

- Myanmar literature

- mysteries

- mythology

- Nahai

- Names

- Namibia

- Namibian fiction

- Namibian literature

- Namibian novels

- Napoleon

- narcissism

- nationalism

- Nauru

- Nauruan books

- Nauruan fiction

- Nauruan literature

- Nauruan novels

- navigation

- Nepal

- Nepalese books

- Nepalese fiction

- Nepalese literature

- Nepali books

- Nepali fiction

- Nepali literature

- Nero

- Netherlands

- Netherlands Antilles

- Netherlands Antilles fiction

- Netherlands Antilles novels

- Netherlands East Indies

- Netherlands fiction

- Netherlands literature

- New Caledonia

- New Caledonian books

- New Caledonian fiction

- New Caledonian literature

- New Caledonian novels

- New Guinea

- New Guinea fiction

- New Guinea literature

- New Zealand

- New Zealand fiction

- New Zealand literature

- Nicaragua

- Nicaraguan fiction

- Nicaraguan literature

- Niger

- Nigerian fiction

- Nigerien fiction

- Nigerien literature

- Nobel Prize for Literature

- nomads

- North African fiction

- North African literature

- North America

- North American fiction

- North American literature

- North Korea

- North Korean fiction

- North Korean literature

- North Yemen

- Northern Ireland

- Northern Irish fiction

- Northern Irish literature

- Northern Macedonia

- Northern Macedonian fiction

- Northern Macedonian literature

- Northern Macedonian novels

- Northern Marianas

- Northern Marianas books

- Northern Marianas fiction

- Northern Marianas literature

- Northern Marianas novels

- Norway

- Norwegian books

- Norwegian fiction

- Norwegian literature

- Norwegian novels

- Notre Dame de Paris

- Novel

- novel from every country

- novelists

- novels

- novels in English

- novels in French

- novels in German

- novels in Italian

- novels in Portuguese

- novels in Spanish

- novels of the world

- Nuclear tests

- Old people

- Oman

- Oman fiction

- Oman literature

- Omar Khayyam

- oral literature

- orphans

- Ottoman Empire

- Pacific Islands

- Pacific Islands books

- Pacific Islands fiction

- Pacific Islands literature

- Pacific Islands novels

- painters

- Pakistan

- Pakistan fiction

- Pakistan literature

- Pakistani fiction

- Pakistani literature

- Palau

- Palau books

- Palau fiction

- Palau literature

- Palau novels

- palynology

- Panama

- Panama Canal

- Panama fiction

- Panama literature

- Panama novel

- pandemics

- Papua

- Papua fiction

- Papua literature

- Papua New Guinea

- Papua New Guinea fiction

- Papua New Guinea literature

- parachutes

- Paradise

- Paraguay

- Paraguay fiction

- Paraguay literature

- paranoia

- parents

- partition

- Patrick White

- Peru

- Peruvian fiction

- Peruvian literature

- pets

- pharaohs

- Philippines

- phosphate

- pigeons

- pilgrimage to Mecca

- piracy

- pirates

- Pitcairn

- Pitcairn Island books

- Pitcairn Island fiction

- Pitcairn Island literature

- Pitcairn Island novels

- plantations

- poetry

- Poland

- police

- Polish fiction

- Polish literature

- politicians

- politics

- pollen

- Polo

- polygamy

- Polygon

- Polynesia

- Polynesian books

- Polynesian fiction

- Polynesian literature

- Polynesian novels

- Portugal

- Portuguese fiction

- Portuguese literature

- poverty

- praise-singers

- Pramoedya Toer

- prejudice

- presidential palace

- presidents

- Pride and Prejudice

- princes

- principalities

- Prisons

- progress

- promiscuity

- prostitution

- Prussia

- psychopaths

- Publishing

- Puerto Rican fiction

- Puerto Rican literature

- Puerto Rican novels

- Puerto Rico

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

- punishment

- Punjab

- Punjab books

- Punjab fiction

- Punjab literature

- Punjab novels

- Qatar

- Qatar fiction

- Qatar literature

- Qatar novels

- Quests

- Race relations

- racism

- radiation sickness

- radicalism

- railways

- Rapa Nui

- rape

- Rasputin

- reading

- Reading 1 book from every country

- Reading 1 novel from every country in the world

- Reading the world

- reconciliation

- redevelopment

- reefs

- refugees

- reincarnation

- religion

- Requiem pour Alain Gerbault

- restaurants

- Reunion

- Reunion fiction

- Reunion literature

- Reunion novels

- revenge

- review

- revolution

- Rhodesia

- Rhodesia fiction

- Rhodesia literature

- Risorgimento

- roads

- Robert Louis Stevenson

- Roman Catholic Church

- Roman Empire

- Romance

- Romania

- Romanian fiction

- Romanian literature

- romantic thriller

- running

- Russia

- Russian fiction

- Russian literature

- Russian novels

- Russian Revolution

- Rwanda

- Rwanda fiction

- Rwanda literature

- Sahel

- sailing

- sailors

- samizdat

- Samoa

- Samoan books

- Samoan fiction

- Samoan literature

- Samoan novels

- San Marino

- San Marino books

- San Marino fiction

- San Marino literature

- San Marino novels

- Sanatoria

- satire

- Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabian fiction

- Saudi Arabian literature

- São Tomé and Príncipe

- São Tomé and Príncipe books

- São Tomé and Príncipe fiction

- São Tomé and Príncipe literature

- São Tomé and Príncipe novels

- Scandinavia

- Scandinavian fiction

- Scandinavian literature

- science

- science fiction

- scientists

- Scotland

- Scottish fiction

- Scottish literature

- sculpture

- Second Coming

- Second World War

- secret police

- Senegal

- Senegal fiction

- Senegalese fiction

- Senegalese literature

- Serbia

- Serbia fiction

- Serbia literature

- servants

- sex

- Seychelles

- Seychelles books

- Seychelles fiction

- Seychelles literature

- Seychelles novels

- Shaka

- shamanism

- Shanshan

- shipbuilding

- shipwrecks

- short stories

- siblings

- Sierra Leone

- Sierra Leone fiction

- Sierra Leone literature

- Sikkim

- Sikkim fiction

- Sikkim literature

- Sikkim novels

- Silk Road

- Singapore

- Singapore fiction

- Singapore literature

- sisters

- Slavery

- sleeper agents

- Slovak fiction

- Slovak literature

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Slovenian fiction

- Slovenian literature

- Slovenian novels

- snakes

- social media

- soldiers

- Solomon Islands

- Solomon Islands fiction

- Solomon Islands literature

- Solomon Islands novels

- Somali books

- Somali novels

- Somalia

- Somalian fiction

- Somalian literature

- Somaliland

- Somaliland books

- Somaliland fiction

- Somaliland literature

- Somaliland novels

- sons

- sorcery

- South Africa

- South African fiction

- South African literature

- South America

- South American books

- South American fiction

- South American literature

- South American novels

- South Korean fiction

- South Korean literature

- South Sudan

- South Sudan books

- South Sudan fiction

- South Sudan literature

- South Sudan novels

- Soviet Union

- space travel

- Spain

- Spanish fiction

- Spanish literature

- speeches

- spies

- spirits

- Spitsbergen

- Spitzbergen

- Sri Lanka

- Sri Lankan fiction

- Sri Lankan literature

- St Helena

- St Helena books

- St Helena fiction

- St Helena literature

- St Helena novel

- St Kitts and Nevis

- St Kitts and Nevis books

- St Kitts and Nevis fiction

- St Kitts and Nevis literature

- St Kitts and Nevis novels

- St Lucia

- St Lucian books

- St Lucian fiction

- St Lucian literature

- St Lucian novels

- St Vincent and the Grenadines

- St Vincent books

- St Vincent fiction

- St Vincent literature

- St Vincent novels

- Stein

- Strikes

- Strindberg

- Sudan

- Sudan books

- Sudan novels

- Sudanese fiction

- Sudanese literature

- sugar

- suicide

- Suriname

- Suriname books

- Suriname fiction

- Suriname literature

- Suriname novels

- Svalbard

- Swazi fiction

- Swazi literature

- Swazi novels

- Swaziland

- Sweden

- Swedish fiction

- Swedish literature

- Swiss fiction

- Swiss literature

- Switzerland

- Switzerland fiction

- Switzerland literature

- Syria

- Syrian fiction

- Syrian literature

- Tahiti

- Tahiti books

- Tahiti fiction

- Tahiti literature

- Tahiti novels

- Taiwan

- Taiwanese fiction

- Taiwanese literature

- Tajikistan

- Tajikistan fiction

- Tajikistan literature

- Taklamakan

- Taliban

- Tanganyika

- Tanzania

- Tanzanian fiction

- Tanzanian literature

- Tataria

- Tatarstan

- Tatarstan books

- Tatarstan fiction

- Tatarstan literature

- Tatarstan novels

- taxation

- teachers

- terrorism

- terrorists

- Thai fiction

- Thai Literature

- Thailand

- This Earth of Mankind

- Thousand and One Nights

- thrillers

- Tibet

- Tibetan fiction

- Tibetan literature

- Timor Leste

- Timor Leste fiction

- Timor Leste literature

- Timor Leste novels

- Togo

- Togo fiction

- Togo literature

- Tonga

- Tongan books

- Tongan fiction

- Tongan literature

- Tongan novels

- torture

- tourism

- tractors

- Trade unions

- trains

- trams

- trauma

- Travel

- treason

- Tripitaka

- truth

- tsars

- Tunisia

- Tunisian fiction

- Tunisian literature

- Turgenev

- Turkey

- Turkish fiction

- Turkish literature

- Turkmenistan

- Turkmenistan books

- Turkmenistan fiction

- Turkmenistan literature

- Turkmenistan novels

- Turks

- Turks and Caicos

- Turks and Caicos books

- Turks and Caicos fiction

- Turks and Caicos literature

- Turks and Caicos novels

- Tuvalu

- Tuvalu books

- Tuvalu fiction

- Tuvalu literature

- Tuvalu novels

- Tuvans

- Uganda

- Ugandan fiction

- Ugandan literature

- Uighuristan

- Ukraine

- Ukrainian fiction

- Ukrainian literature

- Uncategorized

- United Arab Emirates

- United Arab Emirates fiction

- United Arab Emirates literature

- United Kingdom

- United States

- United States fiction

- United States literature

- United States of America

- Uruguay

- Uruguayan fiction

- Uruguayan literature

- Uruguayan novel

- US Virgin Islands

- US Virgin Islands books

- US Virgin Islands fiction

- US Virgin Islands literature

- US Virgin Islands novels

- USA

- USSR

- Uzbek fiction

- Uzbek literature

- Uzbekistan

- Vanuatu

- Vanuatu books

- Vanuatu literature

- Vanuatu novels

- Vatican City

- Vatican City books

- Vatican City fiction

- Vatican City literature

- Vatican City novels

- Venezuela

- Venezuelan books

- Venezuelan fiction

- Venezuelan literature

- Venezuelan novels

- Viet Cong

- Vietnam

- Vietnam War

- Vietnamese books

- Vietnamese literature

- Violence

- virus

- volcanoes

- voodoo

- voting

- voyages

- voyaging

- Wales

- War

- warfare

- watches

- watchmaking

- weather

- Welsh fiction

- Welsh literature

- West Africa

- West African fiction

- West African literature

- West African novels

- West Indies

- West Indies books

- West Indies fiction

- West Indies literature

- West Indies novels

- West Papua

- West Papua fiction

- West Papua literature

- Western Regions

- Western Sahara

- Western Sahara fiction

- Western Sahara literature

- Western Sahara novels

- witch doctors

- witchcraft

- wolves

- women

- world

- world literature

- World War I

- World War II

- writer's block

- writers

- writing

- Xinjiang

- Xinjiang fiction

- Xinjiang literature

- Xiongnu

- Xuanzang

- Yamusangie

- Yemen

- Yemeni fiction

- Yemeni literature

- Yugoslavia

- Yugoslavia fiction

- Yugoslavia literature

- Yugoslavia novels

- Zaire

- Zambia

- Zambian fiction

- Zambian literature

- Zanzibar

- Zimbabwe

- Zimbabwe fiction

- Zimbabwe literature

- zombies

- Zulus

Recent Comments